The Complete Guide to Jazz Chords Piano

Want to spice up your jazz chords? Here is a complete list of the most common ways to make your chords snazzy and juicier than you could imagine.

When you first start playing piano, every note you touch feels like colors. The sensation of the keys under your fingers feels like painting – even the simplest melodies can bring so much bliss. But then, as humans do, we become familiar and get restless.

We want something new that will challenge our minds and ears. If you’re no longer satisfied with the basic major and minor chords, then the time has come to dip your toes into the deep blue waters of jazz.

Keep reading for an in-depth exploration of ways to make your piano chords come alive with the flavors of jazz.

What are chords?

You’re probably already familiar with this, but, just in case, a chord is when you simultaneously play two or more notes. Most piano chords comprise three notes – this is a triad. Adding a fourth or fifth note can achieve a wide range of variations.

Every chord has a sort of personality. The chords you play in a song will determine if it is joyous and celebratory, melancholy and reflective, or angry and frightening. When you play chords in a progression, they become the song’s fabric upon which you can play the melody.

Chords are built from the notes of a scale – a series of 7 notes with a specific intervallic formula. This is a whole topic in and of itself, so you should do your reading on Piano Scales for Beginners if this is unfamiliar to you. To explain how we build piano chords, let’s label the notes in a C major scale from one to seven:

CD E F G A B

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

To build piano chords from this scale, we have to make different combinations of notes. Different chords will use different scale degrees, hence each one’s unique sound. Here is an example of some intermediate chords from the C major scale:

Cmaj7 = C,E,G,B

Dm7 = D,F,A,C

G7 = G,B,D,F

What makes chords jazzy?

Jazz is a vast genre. Academics and musicians have spent years arguing over what jazz music is. We can all agree that jazz musicians like to use chords with lots of notes. This gives jazz music its rich, colorful, and complicated sound quality.

The basic structure of any chord is the formula of a major chord: 1, 3, 5 – the first, third, and fifth degrees. If the chord is minor, you need to flatten the third. For example, the formula for C minor is 1, b3, 5 – C, Eb, G.

These are chord extensions when you add notes to this basic triad structure. The most common extension is the seventh degree of the scale. For example, the chord Cmaj7: 1, 3, 5, 7 – C, E, G, B.

But this is a trick that most pop music has already figured out. It gets jazzy as the numbers go higher – like the 9th, 11th, and 13th degrees. This might sound confusing because a scale only has seven notes. Yeah, it’s somewhat weird. We use these numbers because we refer to notes that extend beyond the basic structure of a triad or seventh chord.

Remember – these degrees of the scale can also be flattened or sharpened. This just blew your chord range wide open. But to simplify it, you should just think of it like this:

9th = 2nd,

11th = 4th,

13th = 6th.

The suspended chord.

Another sound that many jazz and pop artists like to use is the suspended chord. This is when you suspend the third (arguably the most integral and identifying note of a chord) and replace it with either the second or fourth degree. So in C, for example, the suss chords would be:

Csus2 – C, D, G – 1,2,5

Csus4 – C, F, G – 1,4,5

Pro-tip: Chord extensions’ beauty is that they create more options for voice-leading in chords. This is when the chord progression makes incidental (or conscious) melodic lines born from the movement of one chord to the next. For example, the 9th of one chord might become the 3rd of the next chord, and then the 5th of the one after that, and so on, creating a small melodic pattern within the harmonic flow.

Jazzy piano major chords.

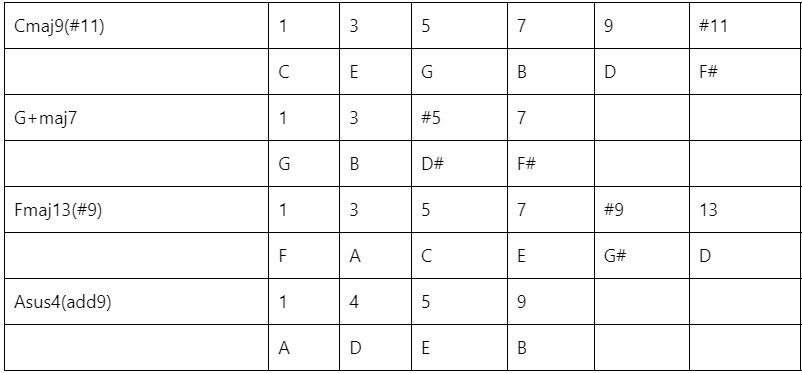

Check out this super sexy and slightly intimidating table of major-sounding jazz chords:

Two important things to remember.

- When the chord symbol says, for example, Cadd9, you add only the 9th and not the 7th. If the symbol says Cmaj9, you add the seventh and the 9th.

- Many of these chords will sound dissonant and dense if you play the notes in the order they are written. Jazz musicians will almost always play some sort of inversion of a chord to make it sound more spread out, even, and digestible. For example, the chord Asus4 (add9). A jazz pianist might play it like this, from lowest to highest:

- A – E in the left hand

- D – B in the right hand

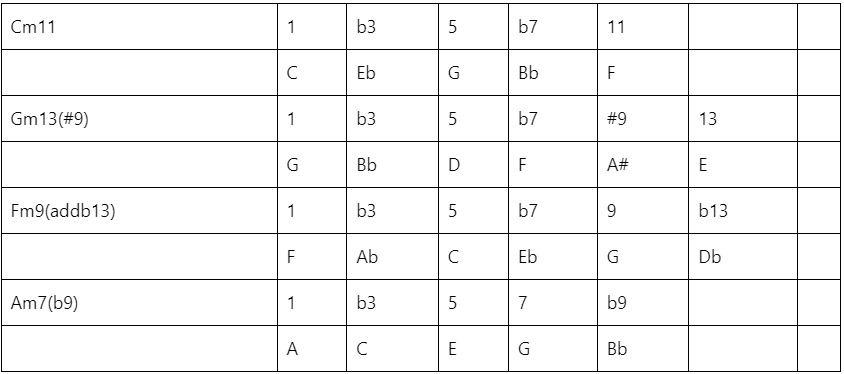

Jazzy piano minor chords.

When the chords get minor, things get messy. (In a good way)

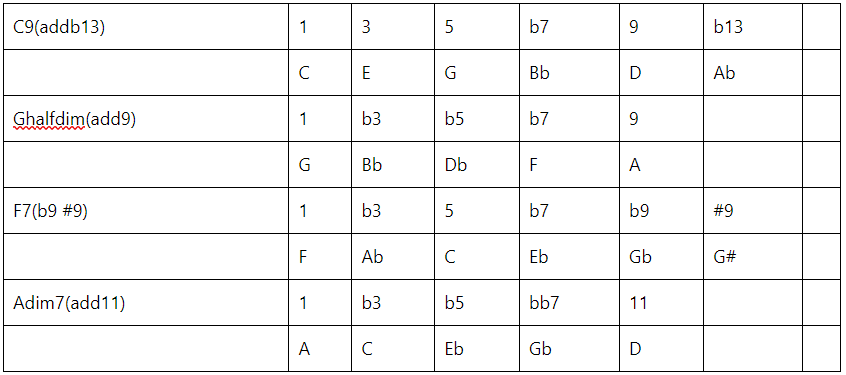

Jazzy piano dominant and diminished chords.

The chords most commonly received extensions are dominant and diminished chords. This is because these usually function as leading chords in some version of a V-I cadence–for example, from G to C or F to Bb.

Leading chords are great for extensions because their job is to create some kind of tension that begs for resolution. The more dense and tense the leading chord, the more sweet and satisfying the resolution.

Keep it simple.

It can be tempting to turn every chord into a wild jazz experiment. But remember, music is not a competition of who made the most sophisticated chord progression.

You don’t make music from the head — it’s from the heart. You want your music to sing, touch people, and resonate.

The beauty of jazz harmony is that it can create lots of detail and emotional nuance, but sometimes simplicity and clarity is the most powerful tool. So study jazz, dive in, and acquire the tools and the language – but once you have, make sure you use them wisely, sparingly, and with heaps of sensitivity.